Leah Stokes gave a webinar in early October with the Clean Energy States Alliance. In the webinar, she discussed her recent publication with Chris Warshaw in Nature Energy.

The webinar was recorded and can be watched here.

Leah Stokes gave a webinar in early October with the Clean Energy States Alliance. In the webinar, she discussed her recent publication with Chris Warshaw in Nature Energy.

The webinar was recorded and can be watched here.

In the Fall issue of the Stanford Social Innovation Review, Leah Stokes' research on Texas' adoption of its renewable energy laws was profiled. As the article summarizes, this research shows that effective philanthropic work uses a combination of insider and outsider funding strategies to drive policy change. Outsider, grassroots groups help get policies on the agenda and build support for their passage. Insider, technical groups are necessary to negotiating specific policy provisions

You can read the full article in the magazine, on the SSIR website, or here.

Duck of Minerva is a prominent academic blog on world politics. Leah Stokes and Matto Mildenberger recently coauthored comments for a forum post on the blog on the likely effects of Harvey and Irma on US politics. The full post can be read here, and a summary of their comments is below.

Q: What are the most important political consequences of Harvey and Irma? Are they a “game changer” for US climate discourse?

No, Harvey and Irma are not game-changers. US climate discourse will only change systematically when Republican elites decide it is in their political interest to engage sincerely with the climate crisis. This is not to say they need agree with Democrats on policy solutions; they simply need to share belief in climate change as a policymaking starting point.

That said, Harvey and Irma do matter. They can create a moment where media attention returns to the dangers of climate change, and brings the issue to the top of the policymaking agenda. Unfortunately, most mainstream news outlets failed to mention climate change during their extensive media coverage, an act activists have dubbed “climate silence.” Thus, a key science communication moment was largely squandered.

The hurricanes also raise the salience of the climate crisis for many Americans–at least in the short term. However, political science research generally shows that experience-induced shifts in climate beliefs and risk perceptions are not durable. Real shifts in discourse and partisan beliefs requires systematic messaging by political elites. So far, it doesn’t seem that Republican elites have revised their messages in response to Harvey and Irma.

Q: What is the role of scientific agencies and organizations is in this “post fact” era?

Facts and science still matter a lot in the post-fact era. For one, scientists and scientific agencies continue to describe and profile human-caused climate change’s real and accelerating dangers. Denying climate change does not change the material facts at hand: increased wildfires, droughts, and severe weather are already disrupting the lives and economic well-being of Americans today. Secondly, once we move below the noise and bluster of federal political debates, scientific assessments and perspectives still shape bureaucratic implementation, regulatory decisions, state and local policy goals and more.

Q: What are the most promising levers for promoting better adaptation policies?

Many adaptation policies can be implemented without specific mention or discussion of climate change—they often fall under infrastructure policy, which tends to be bipartisan. That may be the best option available for planners in some parts of the US today. However, robust mitigation policies are still the most promising way to fund adaptation policies and prevent the need for more costly adaptation.

A focus on adaptation is important – but cannot shortcut the need for the US political system to grapple with an essential fact: human activity is causing climate change and it will damage human health and the economy. Only efforts to reshape this human activity can cost-effectively protect Americans from the social and economic risks associated with global warming.

Matto Mildenberger just published a new policy brief with Mark Lubell at the UC Davis Center for Environmental Policy and Behavior. The brief reports some initial results from a household survey of SF Bay residents regarding their perceptions of sea-level rise and floodrisks, as it relates to various types of political behavior such as voting for ballot propositions that will protect against sea-level rise.

Sea-level rise is psychologically distant concept; the majority of SF Bay residents think it will not harm them personally, while the most significant harm is for future generations and developing countries. People are more likely to support political measures to combat sea-level rise if they perceive more harm from sea-level rise, of if they have a high subjective perception of sea-level rise flood risk. However, objective flood risk based on zip-code level hydrodynamic models appears to have little influence on support for sea-level rise ballot propositions except among more politically sophisticated respondents. This highlights the importance of understanding the origins of sea-level rise risk perceptions, which are a function of both geography and individual psychological and social factors.

As part of the Public Administration Review's (PAR) symposium on Climate Change and Public Administration, Matto Mildenberger published a commentary on the political benefits of inefficient climate policies. Matto argues that, instead of uncritically enacting climate policies with the least marginal costs, policymakers must consider how climate policy options shape the relative political strengths of different actors over time. As he writes:

"Our atmosphere makes no distinction between a molecule of carbon dioxide released by a coal-fired power plant in Wyoming or by a rainforest fire in Brazil. Yet, the choice to target Wyoming coal or Brazilian deforestation has substantial political repercussions: decisions about who should bear the cost of climate mitigation today reshapes who will have political voice during future rounds of climate policymaking."

One counterintuitive result of this research: policies that are inefficient in the short-term may ultimately produce stronger pro-climate coalitions, and consequently stronger climate policy, over the long-term.

Here is the full commentary:

The political benefits of inefficient climate policies

By: Matto Mildenberger

Climate policy instruments tend to be judged by their efficiency: the ability to reduce carbon pollution at the lowest marginal cost. At first glance, this seems sensible. Transitions to a low-carbon economy will involve substantial adjustment costs. Businesses, workers and publics will face economic disruption and shifting prices. How could we ever justify Pareto-dominated policy designs that impose more costs and spend more money to deliver the same level of carbon pollution reduction? Quite reasonably, it turns out. In fact, serious decarbonization efforts may benefit from inefficient climate policies in the short run when these policies also nurture the growth of pro-climate political coalitions over time.

A move away from “efficiency” can be unsettling. Rhetoric about cost efficiency is deeply engrained within climate policymaking debates. Emissions trading schemes promise to deliver carbon pollution reductions at the point of lowest marginal cost. Carbon offsets and other flexibility-increasing policy mechanisms offer attractive alternatives to costly domestic abatement targets. An undifferentiated carbon tax promises to efficiently price the true costs of carbon pollution into various energy sources. These policies, economists argue, mitigate climate risks in a way that minimizes adjustment costs. Underlying their arguments is an assumption that a ton of carbon pollution abated in one part of the world or in one part of the economy is equivalent to a ton of carbon pollution abated in another part of the world or another part of the economy.

Efficiency or Equity?

At one level this is self-evidently true. Our atmosphere makes no distinction between a molecule of carbon dioxide released by a coal-fired power plant in Wyoming or by a rainforest fire in Brazil. Yet, the choice to target Wyoming coal or Brazilian deforestation has substantial substantial political repercussions: decisions about who should bear the cost of climate mitigation today reshapes who will have political voice during future rounds of climate policymaking. Contrary to the constructed reality of economic models, this means one ton of CO2 reduced in one sector in one part of the world is not the same as a ton of CO2 reduced in a different sector in a different part of the world. Why? These tons may have the same direct effect on atmospheric carbon stocks; however, they have different indirect effects on long-term political support for future climate reforms. The right to release carbon pollution into the atmosphere provides an economic subsidy to particular economic actors. When a carbon polluter is exempted from a carbon tax or given generous emissions allowance allocations, or when a country decides to invest in foreign carbon pollution reduction efforts over domestic reductions, this helps maintain that actors’ profitability and enhances their longevity. In other words, policies that eschew cost imposition on carbon polluters risk entrenching the climate-unfriendly economic and political status quo.

For example, Norway was the second country in the world to enact a carbon tax in 1991 but systematically exempted onshore process industries from any costs for over two decades. (While these industries are now part of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, they joined as clear economic winners under that policy’s allowance distribution scheme). At the same time, carbon taxes on the offshore oil industry were calibrated to avoid radical disruption to that industry’s growth. These exemptions stemmed from the outsized political influence of carbon-intensive industries within Norwegian policymaking debates. Reluctant to impose significant costs on domestic producers, more recent Norwegian governments have championed such initiatives as the Climate and Forestry Initiative, policies explicitly designed to fund low marginal cost carbon pollution abatement opportunities outside of Norway. In this way, efficiency rhetoric has allowed successive Norwegian governments to maintain the political and economic status quo. Current carbon pricing reform efforts face the same political opponents as climate reformers faced in the early 1990s. Meanwhile, domestic emissions have increased 3.3% since 1990.

By contrast, inefficient policies can sometimes reshape the distribution of political power when they explicitly redirect resources to new climate policy winners. For example, consider debates over whether renewable energy support policies are desirable after a country passes an emissions trading scheme. In the United States, conservative Democrats opposed the inclusion of a renewable energy standard in the 2009 Waxman-Markey bill because they believed it inefficient and superfluous. Critics suggested the same of Australia’s Clean Energy Finance Corporation, a government-initiated effort to finance clean energy deployment set up in parallel to the country’s emissions trading scheme. According to these critics, mandates for clean energy under a national carbon cap don’t reduce net national emissions; instead, renewable energy deployment simply creates “slack” within allowance markets. In this way, government expenditures on clean energy are wasted on a game of abatement musical chairs without any net mitigation benefits.

Again, this is true in a direct sense. Yet, this criticism neglects a key fact: decisions about the distribution of climate policy costs, even under a cap, have significant political repercussions. When policymakers promote the existence of clean energy businesses, regardless of whether a national carbon cap exists, they nurture new political actors who will mobilize in support of more ambitious future climate policies. Renewable energy support policies promote new political actors that mobilize to support and expand climate and energy reforms. This political benefit can be crucial to long-term decarbonization efforts even if renewable energy support policies are narrowly inefficient in the presence of carbon cap.

Moving beyond marginal abatement costs

In conclusion, public administration scholars need to go beyond merely comparing the marginal abatement costs of different policy instruments, the declaring the one with the lowest to be winner or the desired one. We need to ask whether in some contexts efficiency arguments offer cover for established carbon polluters to avoid domestic costs. Might policies that target higher-cost abatement opportunities facilitate the emergence of new political coalitions to reform existing policies? If it takes inefficient policies in the short-term to support the redistribution of political power in a given economy, will long-term efficiency gains (from the increased political power of pro-climate coalitions) dominate these short-term costs?

The climate threat is not a single-round policy game. It will instead involve repeated rounds of policy bargaining over decades. Consequently, short-term policies must be designed and implemented in a way that generates strategic opportunities for future climate reformers. We must remain open to the possibility that reshaping the balance of domestic political power will cost more than an economist’s estimated least marginal abatement cost. Sometimes it’s the inefficient policies that unlock more effective – and eventually more efficient – decarbonization opportunities over time.

Matto Mildenberger is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University California Santa Barbara.

An essay by Leah Stokes was just published on HistPhil, a web publication centered on the history of philanthropic and nonprofit organizations. Leah's commentary explains how foundations can push for policy more effectively by prioritizing more funding to grassroots NGOs. Her essay profiles the work of the Energy Foundation, which played a key role in pushing for pro-renewable energy policies during the energy restructuring debate of the 1990s. While the Energy Foundation helped fund "insider" technical NGOs to design policy options (like the renewable portfolio standard), She argues that the Foundation's long-term funding of "outsider" grassroots NGOs was equally as important:

"In politics, it’s not enough to come up with a great idea—you also have to get that idea onto the agenda, and create political pressure to pass the policy. While technical groups are skilled at designing and negotiating policies with other political elites, they typically lack the grassroots networks necessary to get the policy signed into law."

To read Leah's full essay, click here.

A new paper has just been published by Leah Stokes and Christopher Warshaw: Renewable energy policy design and framing influence public support in the United States in the journal Nature Energy. This paper analyzes how policy framing shapes public support for energy policies.

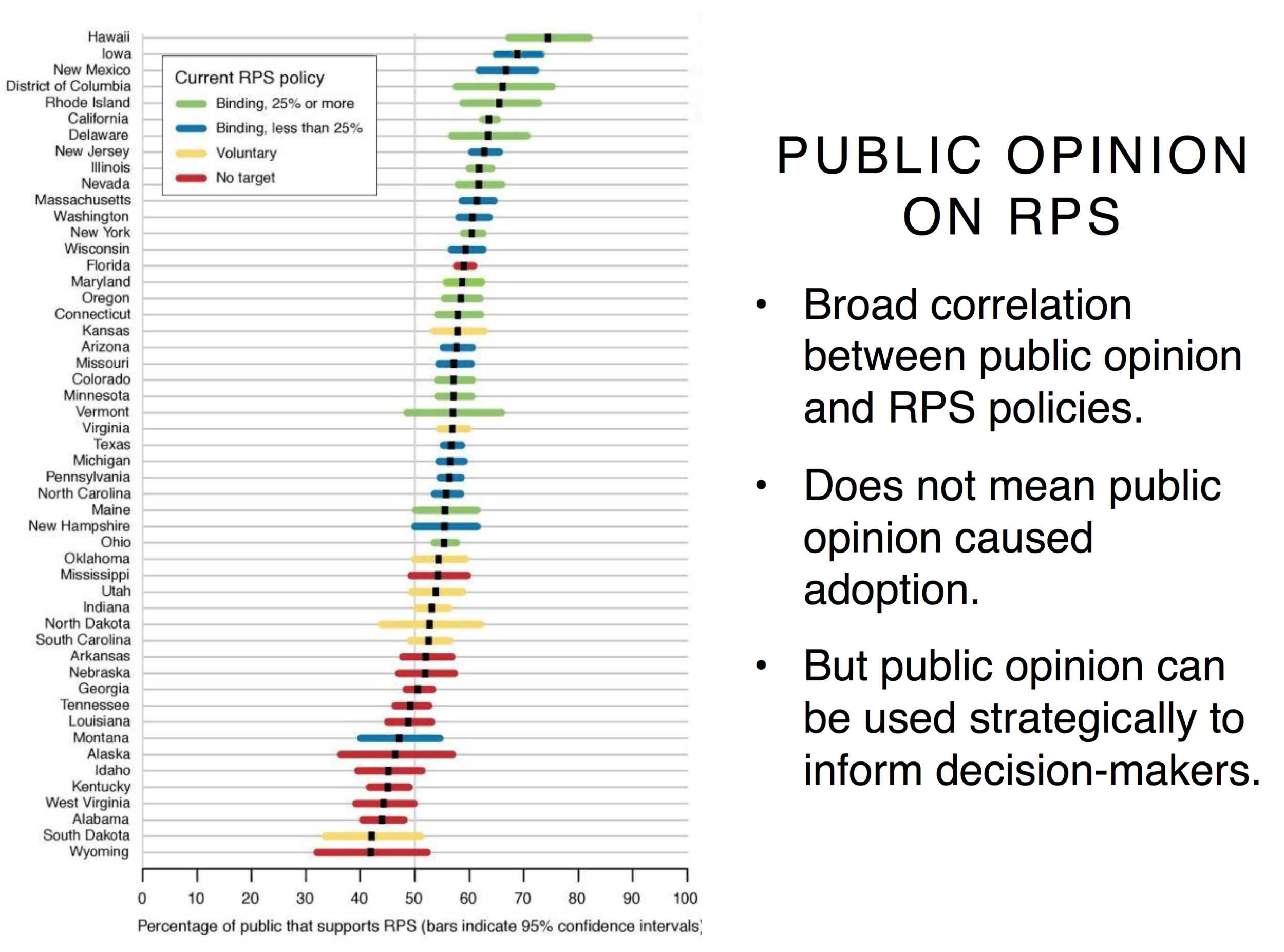

In this paper, we evaluate the congruence between public opinion and state-level renewable energy policy. They find that the presence and ambition of Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) policies tracks public support for RPS policies in each state.

To measure the degree to which different policy frames shape voters' support for RPS bills, we then use a survey experiment to provide respondents different information about how the bill affects air pollution, jobs, energy prices, and climate change. They also varied whether the bill was supported by most Democrat or most Republican legislators. They find that public health, job creation, and partisan cues have significant effects on public support for the RPS; however, positive effects may be limited when voters' electricity bills increase.

A new paper has just been published by Matto Mildenberger and Anthony Leiserowitz: Public opinion on climate change: Is there an economy-environment tradeoff? in the journal Environmental Politics.

Between 2008 and 2012, multiple surveys found that US public beliefs and attitudes about global warming declined by over 10 percentage points. For example, Yale Project on Climate Change Communication surveys found that public belief that global warming is happening fell from 71% in 2008 to a low of 57% in 2010 (Figure 1) before beginning to rebound.

What happened?

Analysts have suggested that a lot of different factors contributed – from weather events to political polarization. And almost everyone has assumed that the Great Recession played a central role. In fact, politicians and academics often assume that public preferences for economic and environmental policies are substitutes. When the economy is bad, the public cares more about short-term economic needs and less about long-term environmental risks. When the economy improves, it provides space for the public to worry more about environmental harm.

Surprisingly, there isn’t a lot of evidence demonstrating this relationship in practice. While several studies find some correlation between economic insecurity and climate opinions, there is no robust evidence that this association is causal. To examine this relationship in the context of climate change, in 2011 we recontacted the individuals who completed our 2008 survey. This allowed us to assess how individual-level climate beliefs and attitudes in the U.S. changed over time. This within-subject data allowed us to evaluate whether the Great Recession caused the declines in US climate beliefs.

The analysis led to a consistent and surprising result: The Great Recession did not change U.S. climate beliefs or attitudes at all. Instead, the change in U.S. climate opinions observed between 2008 and 2011 is better explained by other factors, such as cues from political elites. We found no association between declines in local economic conditions and climate beliefs. Changes in self-reported household income and the degree to which our survey respondents felt they had been impacted by the Great Recession did not predict changes in individuals’ climate change opinions between 2008 and 2011. Neither did state, county or zip-code level unemployment rates. Neither did changes in local housing market conditions or local gas prices. We also found no relationship between declines in local economic conditions and support for various climate policies. Many respondents became less supportive of climate policies between 2008 and 2011– but the individuals who were most hard-hit by the Great Recession were no more likely than others to reduce their support for climate policies.

So what happened? If it wasn’t the Great Recession, why did public climate change beliefs and attitudes decline so dramatically? The likely culprit is a parallel shift in American politics that happened during this time, including the rise of the Tea Party. We found a significant association, for example, between changes in the environmental voting record of a survey respondent’s congressional representative and the shift in a respondent’s climate beliefs and attitudes between 2008 and 2011. Political scientists have long argued that public opinion responds to messages and cues from political elites. Our results are consistent with this theory.

This finding is both good and bad news for climate advocates. On one hand, it suggests that public support for climate policy is unlikely to be affected by even large economic swings. Americans are likely to continue to support climate action in good and bad economic times. However, it also indicates that public opinion on climate change is very sensitive to changes in the Republican and Democratic party platforms and politicians’ talking points. This suggests that engaging Republican leaders in the issue will be important not just to the passage of climate legislation, but to shifting public opinion as well.

For more, read the full publication here or email Matto to receive a copy.

ENVENT lab research by Matto Mildenberger and colleagues at the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication was featured today on the New York Times front page.

Matto's research focuses on developing high-resolution spatial maps of US climate and energy opinions. An updated set of climate opinions maps for 2016 was recently released, including estimates of US public climate opinions at state, congressional district, metropolitan area and county scales. The New York Times story profiled a number of findings from this update.

Leah Stokes received a grant from the California Institute for Water Resources to conduct research on water conservation in residential water districts across California during the recent record drought.

Read more about the grant and research project here.