Publications

2022

The American electric utility industry's role in promoting climate denial, doubt, and delay

Emily L. Williams, Sydney A. Bartone, Emma K. Swanson, and Leah C. Stokes, 2022, Environmental Research Letters

It is now well established that fossil fuel companies contributed to undermining climate science and action. In this paper, we examine the extent to which American electric utilities and affiliated organizations' public messaging contributed to climate denial, doubt, and delay. We examined 188 documents on climate change authored by organizations in and affiliated with the utility industry from 1968 to 2019. Before 1980, electric utilities' messaging was generally in-line with the scientific understanding of climate change. However, from 1990 to 2000, utility organizations founded and funded front groups that promoted climate doubt and denial. After 2000, these front groups were largely shut down, and utility organizations shifted to arguing for delayed action on climate change, by highlighting the responsibility of other sectors and promoting actions other than cleaning up the electricity system. Overall, our results suggest that electric utility industry organizations have promoted messaging designed to avoid taking action on reducing pollution over multiple decades. Notably, many of the utilities most engaged in communicating climate doubt and denial in the past currently have the slowest plans to decarbonize their electricity mix.

The effect of public safety power shutoffs on climate change attitudes and behavioral intentions

Matto Mildenberger, Peter D. Howe, Samuel Trachtman, Leah C. Stokes, & Mark Lubell, 2022, Nature Energy

As climate change accelerates, governments will be forced to adapt to its impacts. The public could respond by increasing mitigation behaviours and support for decarbonization, creating a virtuous cycle between adaptation and mitigation. Alternatively, adaptation could generate backlash, undermining mitigation behaviours. Here we examine the relationship between adaptation and mitigation in the power sector, using the case of California’s public safety power shut-offs in 2019. We use a geographically targeted survey to compare residents living within power outage zones to matched residents in similar neighbourhoods who retained their electricity. Outage exposure increased respondent intentions to purchase fossil fuel generators while it may have reduced intentions to purchase electric vehicles. However, exposure did not change climate policy preferences, including willingness to pay for either wildfire or climate-mitigating reforms. Respondents blamed outages on their utility, not local, state or federal governments. Our findings demonstrate that energy infrastructure disruptions, even when not understood as climate adaptations, can still be consequential for decarbonization trajectories.

Limited impacts of carbon tax rebate programmes on public support for carbon pricing

Matto Mildenberger, Erick Lachapelle, Kathryn Harrison, & Isabel Stadelmann-Steffen, 2022, Nature Climate Change

Revenue recycling through lump-sum dividends may help mitigate public opposition to carbon taxes, yet evidence from real-world policies is lacking. Here we use survey data from Canada and Switzerland, the only countries with climate rebate programmes, to show low public awareness and substantial underestimation of climate rebate amounts in both countries. Information was obtained using a five-wave panel survey that tracked public attitudes before, during and after implementation of Canada’s 2019 carbon tax and dividend policy and a large-scale survey of Swiss residents. Experimental provision of individualized information about true rebate amounts had modest impacts on public support in Switzerland but potentially deleterious effects on support in Canada, especially among Conservative voters. In both countries, we find that perceptions of climate rebates are structured less by informed assessments of economic interest than by partisan identities. These results suggest limited effects of existing rebate programmes, to date, in reshaping the politics of carbon taxation.

Nuclear power and renewable energy are both associated with national decarbonization

Harrison Fell, Alex Gilbert, Jesse D. Jenkins & Matto Mildenberger, 2022, Nature Energy

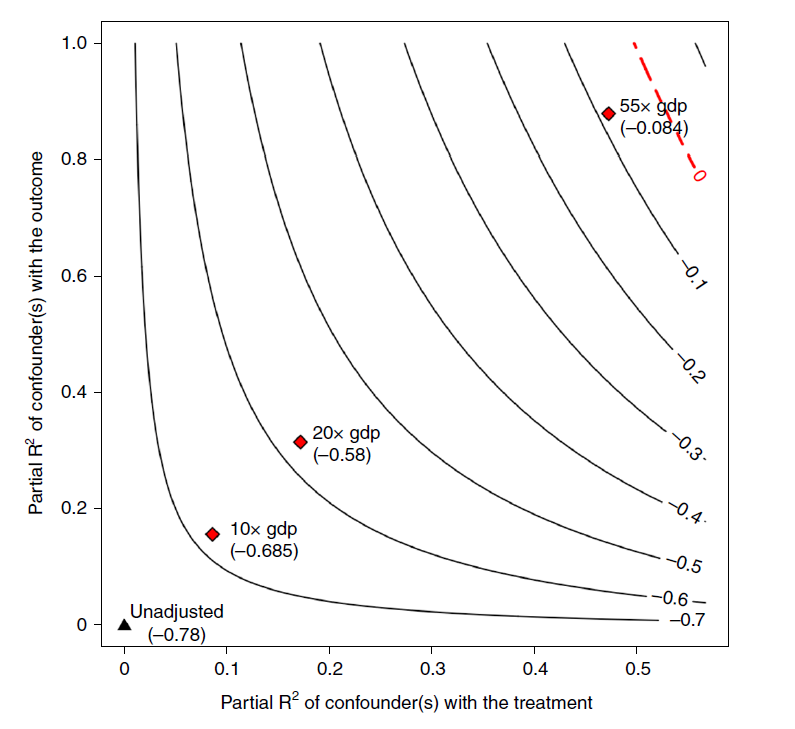

Is nuclear power historically associated with reduced CO2 emissions? We find that nuclear power and renewable energy are both associated with lower per capita CO2 emissions with effects of similar magnitude and statistical significance, which invalidates the central claim of Sovacool et al. We further demonstrate through sensitivity analysis that this association is robust to potential omitted variables. Our empirical analysis thus confirms that nuclear power and renewable electricity alike can both contribute to decarbonization and climate mitigation objectives.

2021

National climate institutions complement targets and policies

Navroz K. Dubash, Aditya Valiathan Pillai, Christian Flachsland, Kathryn Harrison, Kathryn Hochstetler, Matthew Lockwood, Robert MacNeil, Matto Mildenberger, Matthew Paterson, Fei Teng, and Emily Tyler, 2021, Science

Discussions about climate mitigation tend to focus on the ambition of emission reduction targets or the prevalence, design, and stringency of climate policies. However, targets are more likely to translate to near-term action when backed by institutional machinery that guides policy development and implementation. Institutions also mediate the political interests that are often barriers to implementing targets and policies. Yet the study of domestic climate institutions is in its infancy, compared with the study of targets and policies. Existing governance literatures document the spread of climate laws (1, 2) and how climate policy-making depends on domestic political institutions (3–5). Yet these literatures shed less light on how states organize themselves internally to address climate change. To address this question, drawing on empirical case material summarized in table S1, we propose a systematic framework for the study of climate institutions. We lay out definitional categories for climate institutions, analyze how states address three core climate governance challenges—coordination, building consensus, and strategy development—and draw attention to how institutions and national political contexts influence and shape each other. Acontextual “best practice” notions of climate institutions are less useful than an understanding of how institutions evolve over time through interaction with national politics.

The development of climate institutions in the United States

Matto Mildenberger, 2021, Environmental Politics

Climate change poses an existential threat to our planet – but does it require wholesale reorganization of our political institutions? As diverse contributions to this special issue describe, countries have restructured government agencies or developed new institutions to oversee climate reforms. Yet, few such transformations have occurred in the United States, one of the world’s most important cases. Instead, US climate institutions emerged when new mandates and policymaking routines were layered onto existing political institutions. This has had the cumulative effect of creating substantial US climate policymaking capacity in the absence of institutional innovation. When climate proponents have controlled the US presidency, they have mobilized this capacity to center climate change throughout the US executive branch. By contrast, opponents have quickly dismantled climate policy mandates and routines after gaining power. The result has been an unstable variety of climate governance in the United States.

Unilateral climate policies can substantially reduce national carbon pollution

Alice Lépissier and Matto Mildenberger, 2021, Climatic Change

Following the failure of climate governance regimes that sought to impose legally binding treaty-based obligations, the Paris Agreement relies on voluntary actions by individual countries. Yet, there is no guarantee that unilateral policies will lead to a decrease in carbon emissions. Critics worry that voluntary climate measures will be weak and ineffective, and insights from political economy imply that regulatory loopholes are likely to benefit carbon-intensive sectors. Here, we empirically evaluate whether unilateral action can still reduce carbon pollution by estimating the causal effect of the UK’s 2001 Climate Change Programme (CCP) on the country’s carbon emissions. Existing efforts to evaluate the overall impact of climate policies on national carbon emissions rely on Business-As-Usual (BAU) scenarios to project what carbon emissions would have been without a climate policy. We instead use synthetic control methods to undertake an ex post national-level assessment of the UK’s CCP without relying on parametric BAU assumptions and demonstrate the potential of synthetic control methods for climate policy impact evaluation. Despite setting lax carbon targets and making substantial concessions to producers, we show that, in 2005, the UK’s CO2 emissions per capita were 9.8% lower relative to what they would have been if the CCP had not been passed. Our findings offer empirical confirmation that unilateral climate policies can still reduce carbon emissions, even in the absence of a binding global climate agreement and in the presence of regulatory capture by industry.

Conducting the Heavenly Chorus: Constituent Contact and Provoked Petitioning in Congress

Geoffrey Henderson, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, Matto Mildenberger, and Leah C. Stokes, 2021, Perspectives on Politics

Congress hears more and more from everyday citizens. How do modern Congressional offices use this information to represent their constituents? Drawing on original interviews and a survey of Congressional staff, we explore how representation works in practice when new data and tools, such as databases and downscaled public opinion polls, are available. In contrast with established theories that focus on responsiveness, we show that representation is a two-way street. Congressional offices both respond to incoming constituent opinion and reach out to elicit opinions from stakeholders. Offices record correspondence into databases, identifying the most salient issues and the balance of opinion among correspondents. They tend not to use polls on policy. To understand the opinions of electorally influential constituencies, staffers also proactively reach out to stakeholders and experts in a practice we call provoked petitioning. If the Washington pressure system is a chorus, Congressional staff often serve as conductors, allowing well-resourced and organized constituents, including interest groups, to sing with the loudest voices. While Congress has some new tools and strategies for representation, its modern practices still reinforce existing biases.

2020

2019

Prisoners of the wrong dilemma: Why distributive conflict, not collective action, characterizes the politics of climate change

Michaël Aklin and Matto Mildenberger, 2020, Global Environmental Politics

Climate change policy is generally modeled as a global collective action problem structured by free-riding concerns. Drawing on quantitative data, archival work, and elite interviews, we review empirical support for this model and find that the evidence for its claims is weak relative to the theory’s pervasive influence. We find, first, that the strongest collective action claims appear empirically unsubstantiated in many important climate politics cases. Second, collective action claims—whether in their strongest or in more nuanced versions—appear observationally equivalent to alternative theories focused on distributive conflict within countries. We argue that extant patterns of climate policy making can be explained without invoking free-riding. Governments implement climate policies regardless of what other countries do, and they do so whether a climate treaty dealing with free-riding has been in place or not. Without an empirically grounded model for global climate policy making, institutional and political responses to climate change may ineffectively target the wrong policy-making dilemma. We urge scholars to redouble their efforts to analyze the empirical linkages between domestic and international factors shaping climate policy making in an effort to empirically ground theories of global climate politics. Such analysis is, in turn, the topic of this issue’s special section.

Wildfire exposure increases pro-environment voting within Democratic but not Republican areas

Chad Hazlett and Matto Mildenberger, 2020, American Political Science Review

One political barrier to climate reforms is the temporal mismatch between short-term policy costs and long-term policy benefits. Will public support for climate reforms increase as climate-related disasters make the short-term costs of inaction more salient? Leveraging variation in the timing of Californian wildfires, we evaluate how exposure to a climate-related hazard influences political behavior rather than self-reported attitudes or behavioral intentions. We show that wildfires increased support for costly, climate-related ballot measures by 5 to 6 percentage points for those living within 5 kilometers of a recent wildfire, decaying to near zero beyond a distance of 15 kilometers. This effect is concentrated in Democratic-voting areas, and it is nearly zero in Republican-dominated areas. We conclude that experienced climate threats can enhance willingness-to-act but largely in places where voters are known to believe in climate change.

Scientists’ political behaviors are not driven by individual-level government benefits

Matto Mildenberger and Baobao Zhang, 2020, PLOS One

Is it appropriate for scientists to engage in political advocacy? Some political critics of scientists argue that scientists have become partisan political actors with self-serving financial agendas. However, most scientists strongly reject this view. While social scientists have explored the effects of science politicization on public trust in science, little empirical work directly examines the drivers of scientists’ interest in and willingness to engage in political advocacy. Using a natural experiment involving the U.S. National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (NSF-GRF), we causally estimate for the first time whether scientists who have received federal science funding are more likely to engage in both science-related and non-science-related political behaviors. Comparing otherwise similar individuals who received or did not receive NSF support, we find that scientists’ preferences for political advocacy are not shaped by receiving government benefits. Government funding did not impact scientists’ support of the 2017 March for Science nor did it shape the likelihood that scientists donated to either Republican or Democratic political groups. Our results offer empirical evidence that scientists’ political behaviors are not motivated by self-serving financial agendas. They also highlight the limited capacity of even generous government support programs to increase civic participation by their beneficiaries.

Short Circuiting Policy: Interest Groups and the Battle Over Clean Energy and Climate Policy in the American States

Leah C. Stokes, 2020, Oxford University Press

In 1999, Texas passed a landmark clean energy law, beginning a groundswell of new policies that promised to make the US a world leader in renewable energy. As Leah Stokes shows in Short Circuiting Policy, however, that policy did not lead to momentum in Texas, which failed to implement its solar laws or clean up its electricity system. Examining clean energy laws in Texas, Kansas, Arizona, and Ohio over a thirty-year time frame, Stokes argues that organized combat between advocate and opponent interest groups is central to explaining why states are not on track to address the climate crisis. She tells the political history of our energy institutions, explaining how fossil fuel companies and electric utilities have promoted climate denial and delay. Stokes further explains the limits of policy feedback theory, showing the ways that interest groups drive retrenchment through lobbying, public opinion, political parties and the courts. More than a history of renewable energy policy in modern America, Short Circuiting Policy offers a bold new argument about how the policy process works, and why seeming victories can turn into losses when the opposition has enough resources to roll back laws.

Combining climate, economic, and social policy builds public support for climate action in the US

Parrish Bergquist, Matto Mildenberger and Leah Stokes. 2020 Environmental Research Letters

Despite the gravity of the climate threat, governments around the world have struggled to pass and implement climate policies. Today, politicians and advocates are championing a new idea: linking climate policy to other economic and social reforms. Will this approach generate greater public support for climate action? Here, we test this coalition-building strategy. Using two conjoint experiments on a representative sample of 2,476 Americans, we evaluate the marginal impact of 40 different climate, social, and economic policies on support for climate reforms. Overall, we find climate policy bundles that include social and economic reforms such as affordable housing, a $15 minimum wage, or a job guarantee increase US public support for climate mitigation. Clean energy standards, regardless of which technologies are included, also make climate policy more popular. Linking climate policy to economic and social issues is particularly effective at expanding climate policy support among people of color.

Carbon Captured: How Business and Labor Control Climate Politics

Matto Mildenberger, 2020, MIT Press

Climate change threatens the planet, and yet policy responses have varied widely across nations. Some countries have undertaken ambitious programs to stave off climate disaster, others have done little, and still others have passed policies that were later rolled back. In this book, Matto Mildenberger opens the “black box” of domestic climate politics, examining policy making trajectories in several countries and offering a theoretical explanation for national differences in the climate policy process.

Mildenberger introduces the concept of double representation―when carbon polluters enjoy political representation on both the left (through industrial unions fearful of job loss) and the right (through industrial business associations fighting policy costs)―and argues that different climate policy approaches can be explained by the interaction of climate policy preferences and domestic institutions. He illustrates his theory with detailed histories of climate politics in Norway, the United States, and Australia, along with briefer discussions of policies in in Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Canada. Ultimately, Mildenberger argues for the importance of political considerations in understanding the climate policymaking process and discusses possible future policy directions.

Quota sampling using Facebook advertisements

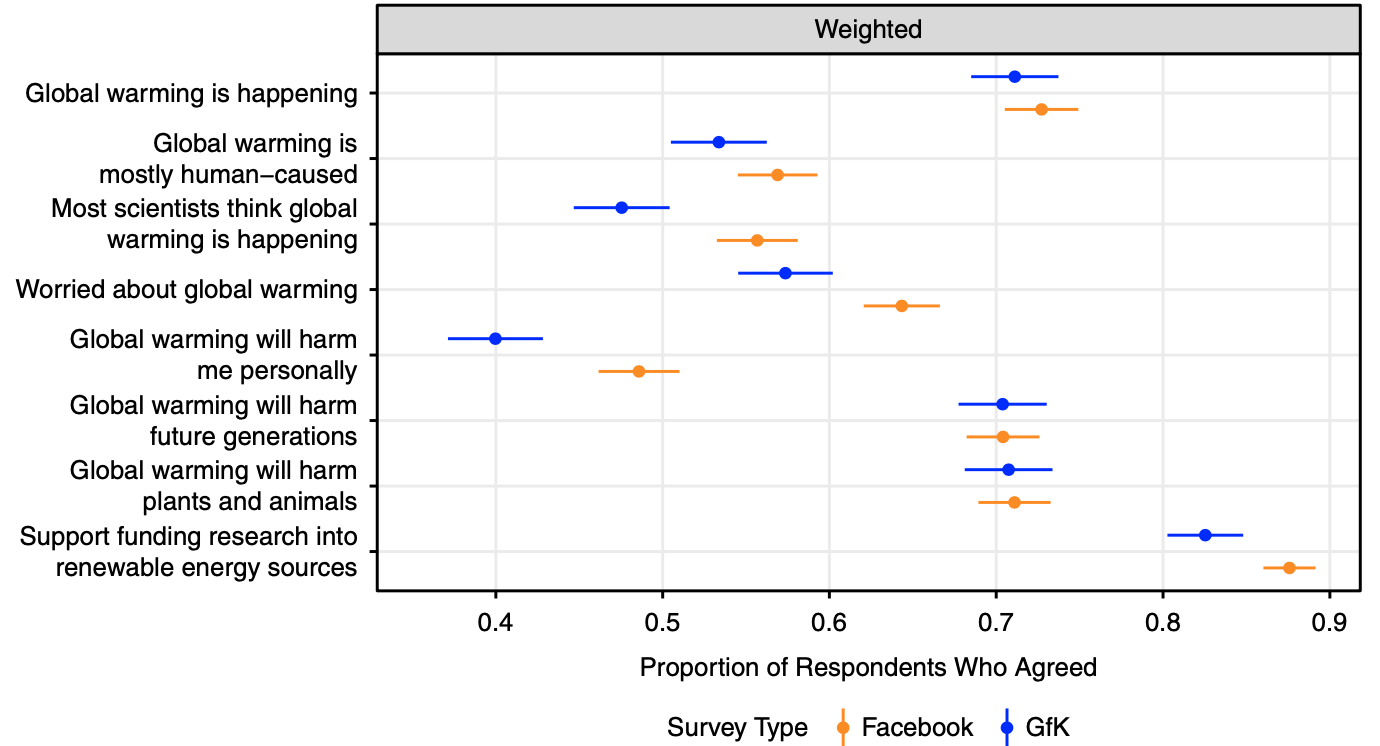

Baobao Zhang, Matto Mildenberger, Peter D. Howe, Jennifer Marlon, Seth A. Rosenthal and Anthony Leiserowitz. 2020. Political Science Research Methods

Researchers in different social science disciplines have successfully used Facebook to recruit subjects for their studies. However, such convenience samples are not generally representative of the population. We developed and validated a new quota sampling method to recruit respondents using Facebook advertisements. Additionally, we published an R package to semi-automate this quota sampling process using the Facebook Marketing API. To test the method, we used Facebook advertisements to quota sample 2432 US respondents for a survey on climate change public opinion. We conducted a contemporaneous nationally representative survey asking identical questions using a high-quality online survey panel whose respondents were recruited using probability sampling. Many results from the Facebook-sampled survey are similar to those from the online panel survey; furthermore, results from the Facebook-sampled survey approximate results from the American Community Survey (ACS) for a set of validation questions. These findings suggest that using Facebook to recruit respondents is a viable option for survey researchers wishing to approximate population-level public opinion.

Households with solar installations are ideologically diverse and more politically active than their neighbors

Matto Mildenberger, Peter Howe and Chris Miljanich. 2019 Nature Energy

Climate risk mitigation requires rapid decarbonization of energy infrastructure, a task that will need political support from mass publics. Here, we use a combination of satellite imagery and voter file data to examine the political identities of US households with residential solar installations. We find that solar households are slightly more likely to be Democratic; however, this imbalance stems primarily from between-neighbourhood differences in partisan composition rather than within-neighbourhood differences in the rate of partisan solar uptake. Crucially, we still find that many solar households are Republican. We also find that solar households are substantially more likely to be politically active than their neighbours, and that these differences in political participation cannot be fully explained by demographic and socioeconomic factors. Our results demonstrate that individuals across the ideological spectrum are participating in the US energy transition, despite extreme ideological polarization around climate change.

How will climate change shape climate opinion?

Matto Mildenberger, Peter Howe, Jennifer Marlon and Brittany Shield. 2019. Environmental Research Letters.

As climate change intensifies, global publics will experience more unusual weather and extreme weather events. How will individual experiences with these weather trends shape climate change beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors? In this article, we review 73 papers that have studied the relationship between climate change experiences and public opinion. Overall, we find mixed evidence that weather shapes climate opinions. Although there is some support for a weak effect of local temperature and extreme weather events on climate opinion, the heterogeneity of independent variables, dependent variables, study populations, and research designs complicate systematic comparison. To advance research on this critical topic, we suggest that future studies pay careful attention to differences between self-reported and objective weather data, causal identification, and the presence of spatial autocorrelation in weather and climate data. Refining research designs and methods in future studies will help us understand the discrepancies in results, and allow better detection of effects, which have important practical implications for climate communication. As the global population increasingly experiences weather conditions outside the range of historical experience, researchers, commu- nicators, and policymakers need to understand how these experiences shape-and are shaped by-public opinions and behaviors.

Personalized risk messaging can reduce climate concerns

Matto Mildenberger, Mark Lubell and Michelle Hummell. 2019. Global Environmental Change.

One potential barrier to climate policy action is that individuals view climate change as a problem for people in other parts of the world or for future generations. As some scholars argue, risk messaging strategies that make climate change personally relevant may help overcome this barrier. In this article, we report a large-n survey experiment on San Francisco Bay Area residents to investigate how providing spatially-resolved risk information to individuals shapes their climate risk perceptions in the context of sea-level rise. Our results suggest that personalized risk messaging can sometimes reduce concern about sea-level rise. These experimental effects are limited to respondents who believe that climate change is happening. Further, we do not find an effect of providing local risk messages on an individual's willingness to pay for regional climate adaptation measures. Our results emphasize that local messaging strategies around sea-level rise risks may not have the clear impacts that some advocates and scholars presume.

Legislative staff and representation in Congress

Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, Matto Mildenberger and Leah C. Stokes. 2019. American Political Science Review.

Legislative staff link Members of Congress and their constituents, theoretically facilitating democratic representation. Yet, little research has examined whether Congressional staff actually recognize the preferences of their Members’ constituents. Using an original survey of senior US Congressional staffers, we show that staff systematically mis-estimate constituent opinions. We then evaluate the sources of these misperceptions, using observational analyses and two survey experiments. Staffers who rely more heavily on conservative and business interest groups for policy information have more skewed perceptions of constituent opinion. Egocentric biases also shape staff perceptions. Our findings complicate assumptions that Congress represents constituent opinion, and help to explain why Congress often appears so unresponsive to ordinary citizens. We conclude that scholars should focus more closely on legislative aides as key actors in the policymaking process, both in the United States and across other advanced democracies.

Energy politics in North America

Matto Mildenberger and Leah C. Stokes. 2019. Oxford Handbook of Energy Politics

Energy resource debates sit at the center of both policymaking and electoral battles across North America. Yet in contrast to Europe, strong international institutions to manage continental energy policy have not developed. Instead, North American energy politics are shaped by four key factors: the federalist nature of North American countries, the absence of effective continental energy institutions, regional economic interdependence, and the relative power asymmetries between the United States and its neighbors, Canada and Mexico. Taken together, these features of North American energy regionalism distinguish it in both form and dynamics from energy politics in Europe and Asia. The North American energy system is an example of regional energy management in which a single dominant state pulls neighbors into a fragmented institutional framework.

Beliefs about climate beliefs: The problem of second-order opinions in climate policymaking

Matto Mildenberger and Dustin Tingley. 2019. British Journal of Political Science

When political action entails individual costs but group-contingent benefits, political participation may depend on an individual’s perceptions of others’ beliefs; yet, detailed empirical attention to these second-order beliefs – beliefs about the beliefs of others – remains rare. We offer the first comprehensive examination of the distribution and content of second-order climate beliefs in the United States and China, drawing from six new opinion surveys of mass publics, political elites, and intellectual elites. We demonstrate that all classes of political actors have second-order beliefs characterized by egocentric bias and global underestimation of pro-climate positions. We then demonstrate experimentally that individual support for pro-climate policies increases after respondents update their second-order beliefs. We conclude that scholars should focus more closely on second-order beliefs as a key factor shaping climate policy inaction and that scholars can use the climate case to extend their understanding of second-order beliefs more broadly.

2018

The politics logics of clean energy transitions

Hanna Breetz, Matto Mildenberger and Leah C. Stokes. 2018. Business & Politics.

Technology costs and deployment rates, represented in experience curves, are typically seen as the main factors in the global clean energy transition from fossil fuels towards low-carbon energy sources. We argue that politics is the hidden dimension of technology experience curves, as it affects both costs and deployment. We draw from empirical analyses of diverse North American and European cases to describe patterns of political conflict surrounding clean energy adoption across a variety of technologies. Our analysis highlights that different political logics shape costs and deployment at different stages along the experience curve. The political institutions and conditions that nurture new technologies into economic winners are not always the same conditions that let incumbent technologies become economic losers. Thus, as the scale of technology adoption moves from niches towards systems, new political coalitions are necessary to push complementary system-wide technology. Since the cost curve is integrated globally, different countries can contribute to different steps in the transition as a function of their individual comparative political advantages.

Reducing the Cost of Voting: An Evaluation of Internet Voting’s Effect on Turnout

Nicole Goodman and Leah C. Stokes. 2018. British Journal of Political Science.

Voting models assume that voting costs impact turnout. As turnout declined across advanced democracies, governments enacted reforms designed to reduce costs in order to increase participation. Internet voting, used in elections across a dozen countries, promises to reduce voting costs dramatically. Yet identifying its effect on turnout has proven difficult. In this article, we use original panel data of local elections in Ontario, Canada and fixed effects estimators to estimate internet voting’s effect. The results show internet voting can increase turnout by 3.5 percentage points, with larger increases when vote by mail (VBM) is not yet adopted, and greater use when registration is not required. Our estimates suggest that internet voting is unlikely to solve the low turnout crisis, and imply that cost arguments do not fully account for recent turnout declines.

Experimental effects of climate messages vary geographically

Baobao Zhang, Sander Van Der Linden, Matto Mildenberger, Jennifer Marlon, Peter Howe and Anthony Leiserowitz. 2018. Nature Climate Change.

Social science scholars routinely evaluate the efficacy of diverse climate frames using local convenience or nationally representative samples. For example, previous research has focused on communicating the scientific consensus on climate change, which has been identified as a ‘gateway’ cognition to other key beliefs about the issue. Importantly, although these efforts reveal average public responsiveness to particular climate frames, they do not describe variation in message effectiveness at the spatial and political scales relevant for climate policymaking. Here we use a small-area estimation method to map geographical variation in public responsiveness to information about the scientific consensus as part of a large-scale randomized national experiment (n = 6,301). Our survey experiment finds that, on average, public perception of the consensus increases by 16 percentage points after message exposure. However, substantial spatial variation exists across the United States at state and local scales. Crucially, responsiveness is highest in more conservative parts of the country, leading to national convergence in perceptions of the climate science consensus across diverse political geographies. These findings not only advance a geographical understanding of how the public engages with information about scientific agreement, but will also prove useful for policymakers, practitioners and scientists engaged in climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Convergence and Divergence in the Study of Ideology: A Critical Review

Jonathan Leader-Maynard & Matto Mildenberger. 2016. British Journal of Political Science.

Dedicated research on ideology has proliferated over the last few decades. Many different disciplines and methodologies have sought to make a contribution, with the welcome consequence that specialist thinking about ideology is at a high-water mark of richness, diversity and theoretical sophistication. Yet this proliferation of research has fragmented the study of ideology by producing independent communities of scholars differentiated by geographical location and by disciplinary attachment. This review draws together research on ideology from several disciplines on different sides of the Atlantic, in order to address three questions that appear to be of great relevance to political scientists: (1) What do we mean by ideology? (2) How do we model ideology? (3) Why do people adopt the ideologies they do? In doing so, it argues that many important axes of debate cut across disciplinary and geographic boundaries, and points to a series of significant intellectual convergences that offer a framework for productive interdisciplinary engagement and integration.

2017

Politics in the U.S. energy transition: Case studies of solar, wind, biofuels and electric vehicles policy

Leah Stokes and Hanna Breetz. 2017. Energy Policy.

We examine the politics of US state and federal policy supporting wind and solar in the electricity sector and biofuels and electric vehicles in the transportation sector. For each technology, we provide two policy case studies: the federal Production Tax Credit (PTC) and state Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) for wind; state Net Energy Metering (NEM) and the federal investment tax credit (ITC) for solar; federal excise tax incentives and the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) for biofuels; and California's Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) mandate and federal tax incentives for electric vehicles. Each case study traces the enactment and later revision of the policy, typically over a period of twenty-five years. We use these eight longitudinal case studies to identify common patterns in the politics of US renewable energy policy. Although electricity and transportation involve different actors and technologies, we find similar patterns across these sectors: immature technology is underestimated or misunderstood; large energy bills provide windows of opportunity for enactment; once enacted, policies are extended incrementally; there is increasing politicization as mature technology threatens incumbents.

The spatial distribution of Republican and Democratic climate opinions at state and local scales

Matto Mildenberger, Jennifer Marlon, Peter Howe and Anthony Leiserowitz. 2017. Climatic Change

Even as US partisan polarization shapes climate and energy attitudes, substantial heterogeneity in climate opinions still exists among both Republicans and Democrats. To date, our understanding of this partisan heterogeneity has been limited to analysis of national- or, less commonly, state-level opinion poll subsamples. However, the dynamics of political representation and issue commitments play out over more finely resolved state and local scales. Here we use previously validated multilevel regression and post-stratification (MRP) models (Howe et al., Nat Clim Chang 5(6):596–603 2015; Mildenberger et al., PLoS One 11(8):e0159774 2016) combined with a novel approach to measuring the distribution of party members to model, for the first time, the spatial distribution of partisan climate and energy opinions. We find substantial geographic variation in Republican climate opinions across states and congressional districts. While Democratic party members consistently think human-caused global warming is happening and support climate policy reforms, the intensity of their climate beliefs also varies spatially at state and local scales. These results have policy-relevant implications for the trajectory of US climate policy reforms.

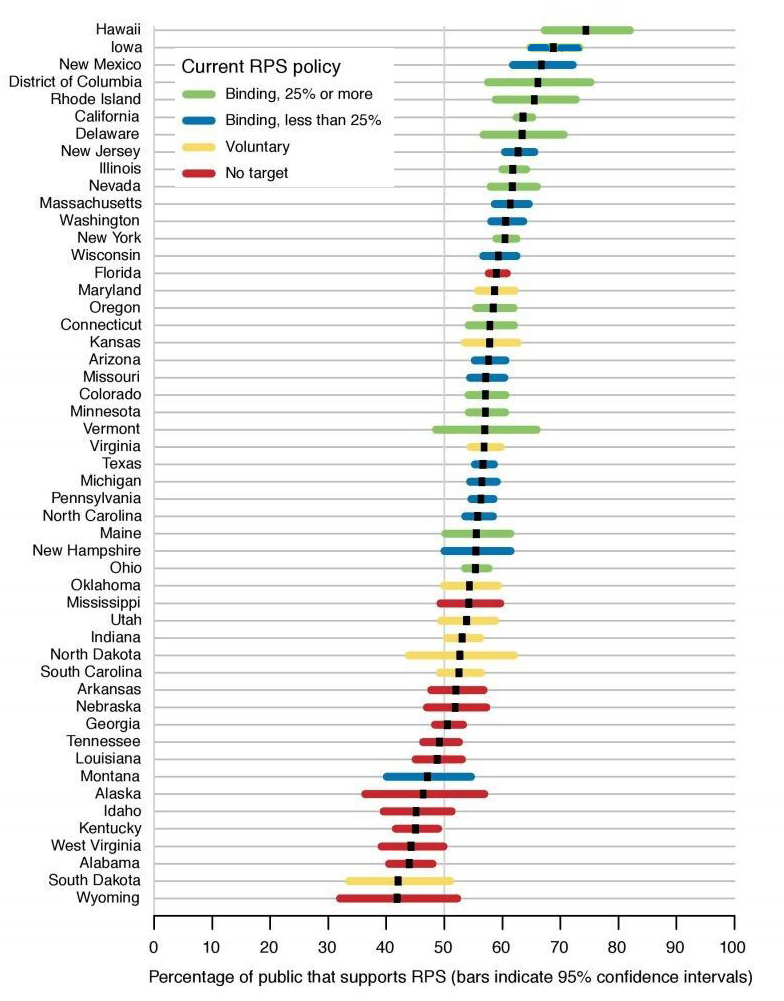

Renewable energy policy design and framing influence public support in the United States

Leah C. Stokes and Christopher Warshaw. 2017. Nature Energy.

The United States has often led the world in supporting renewable energy technologies at both the state and federal level. However, since 2011 several states have weakened their renewable energy policies. Public opinion will probably be crucial for determining whether states expand or contract their renewable energy policies in the future. Here we show that a majority of the public in most states supports renewable portfolio standards, which require a portion of the electricity mix to come from renewables. However, policy design and framing can strongly influence public support. Using a survey experiment, we show that effects of renewable portfolio standards bills on residential electricity costs, jobs and pollution, as well as bipartisan elite support, are all important drivers of public support. In many states, these bills’ design and framing can push public opinion above or below majority support.

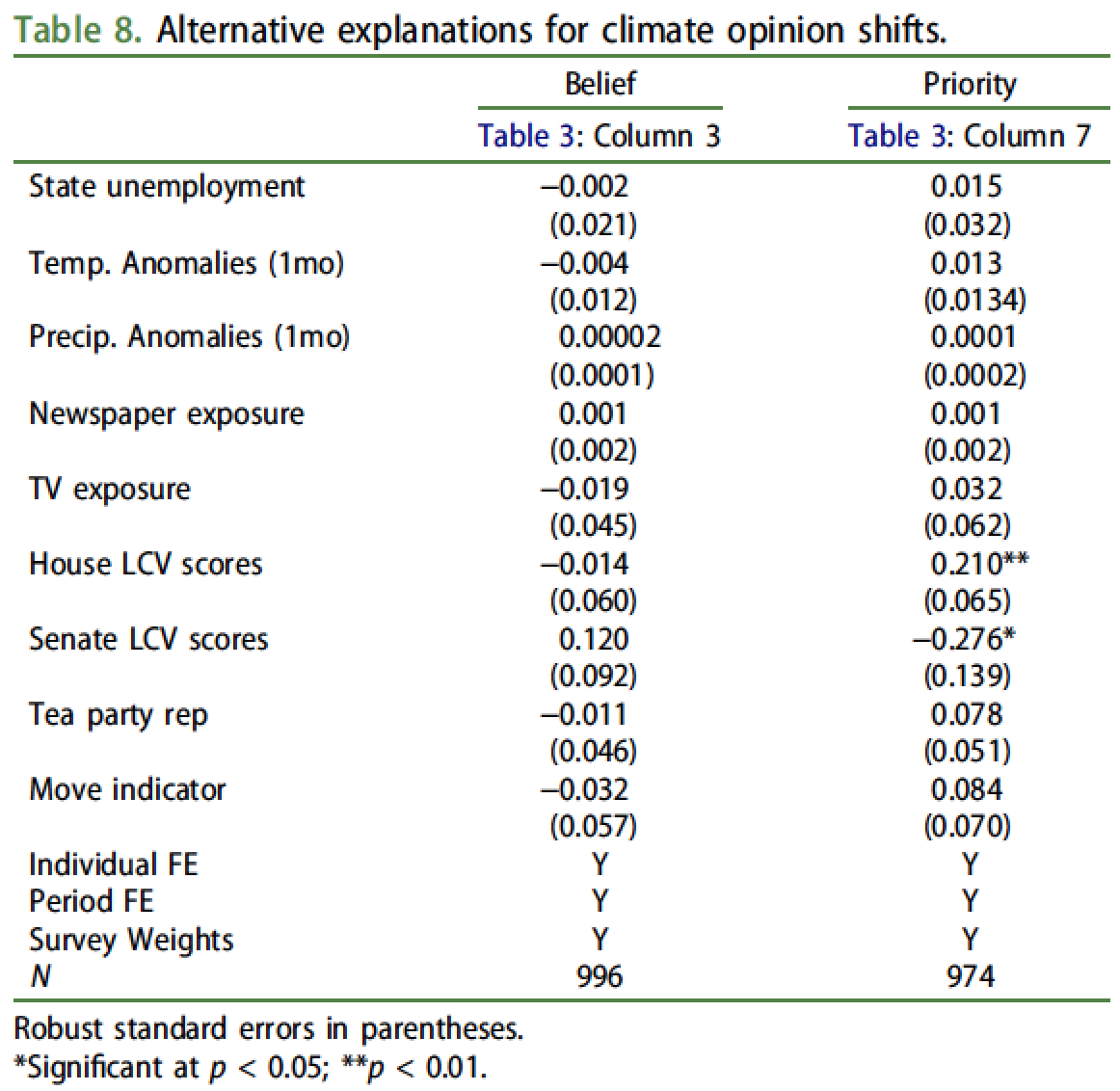

Public opinion on climate change: Is there an economy–environment tradeoff?

Matto Mildenberger and Anthony Leiserowitz. 2017. Environmental Politics.

Does the state of the economy condition public concern for the environment? Scholars have long argued that environmental preferences decline during economic downturns as individuals prioritize short-term economic needs over longer-term environmental concerns. Yet, this assumption has rarely been subjected to rigorous empirical scrutiny at the individual level. The presumed link between economic and environmental preferences is revisited, using the first individual-level opinion panel (n = 1043) of US climate attitudes, incorporating both self-reported and objective economic data. In contrast with prior studies that emphasize the role of economic downturns in driving environmental preference shifts, using a stronger identification strategy, there is little evidence that changes in either individual economic fortunes or local economic conditions are associated with decreased belief that climate change is happening or reduced prioritization of climate policy action. Instead, the evidence suggests that climate belief declines are associated with shifting political cues. These findings have important implications for understanding the dynamics of political conflict over environmental policy globally.

2016

Electoral Backlash against Climate Policy: A Natural Experiment on Retrospective Voting and Local Resistance to Public Policy

Leah C. Stokes. 2016. American Journal of Political Science.

Retrospective voting studies typically examine policies where the public has common interests. By contrast, climate policy has broad public support but concentrated opposition in communities where costs are imposed. This spatial distribution of weak supporters and strong local opponents mirrors opposition to other policies with diffuse public benefits and concentrated local costs. I use a natural experiment to investigate whether citizens living in proximity to wind energy projects retrospectively punished an incumbent government because of its climate policy. Using both fixed effects and instrumental variable estimators, I identify electoral losses for the incumbent party ranging from 4 to 10%, with the effect persisting 3 km from wind turbines. There is also evidence that voters are informed, only punishing the government responsible for the policy. I conclude that the spatial distribution of citizens' policy preferences can affect democratic accountability through ‘spatially distorted signalling’, which can exacerbate political barriers to addressing climate change.

Splitting the South: China and India's Divergence in International Environmental Negotiations

Leah C. Stokes, Amanda Giang and Noelle E. Selin. 2016. Global Environmental Politics.

International environmental negotiations often involve conflicts between developed and developing countries. However, considering environmental cooperation in a North-South dichotomy obscures important variation within the Global South, particularly as emerging economies become more important politically, economically, and environmentally. This article examines change in the Southern coalition in environmental negotiations, using the recently concluded Minamata Convention on Mercury as its primary case. Focusing on India and China, we argue that three key factors explain divergence in their positions as the negotiations progressed: domestic resources and regulatory politics, development constraints, and domestic scientific and technological capacity. We conclude that the intersection between scientific and technological development and domestic policy is of increasing importance in shaping emerging economies’ engagement in international environmental negotiations. We also discuss how this divergence is affecting international environmental cooperation on other issues, including the ozone and climate negotiations.

The Need for Climate Science Education to Build Policy Literacy

Noelle E. Selin, Leah C. Stokes, & Lawrence E. Susskind. 2016. WIREs Climate Change.

An increased focus on ‘policy literacy’ for climate scientists, parallel to ‘science literacy’ for the public, is a critical need in closing the science–society gap in addressing climate mitigation. We define policy literacy as the knowledge and understanding of societal and decision-making contexts required for conducting and communicating scientific research in ways that contribute to societal well-being. We argue that current graduate education for climate scientists falls short in providing policy literacy. We identify resources and propose approaches to remedy this, arguing that policy literacy education needs to be mainstreamed into climate science curricula. Based on our experience training science students in global environmental policy, we propose that policy literacy modules be developed for application in climate science curricula, including simulations, case studies, or hands-on policy experiences. The most effective policy literacy modules on climate change will be hands-on, comprehensive, and embedded into scientific education.

The Distribution of Climate Change Public Opinion in Canada

Matto Mildenberger, Peter Howe, Erick Lachapelle, Leah Stokes, Jennifer Marlon, Timothy Gravelle. 2016. PLOS ONE.

While climate scientists have developed high resolution data sets on the distribution of climate risks, we still lack comparable data on the local distribution of public climate change opinions. This paper provides the first effort to estimate local climate and energy opinion variability outside the United States. Using a multi-level regression and post-stratification (MRP) approach, we estimate opinion in federal electoral districts and provinces. We demonstrate that a majority of the Canadian public consistently believes that climate change is happening. Belief in climate change’s causes varies geographically, with more people attributing it to human activity in urban as opposed to rural areas. Most prominently, we find majority support for carbon cap and trade policy in every province and district. By contrast, support for carbon taxation is more heterogeneous. Compared to the distribution of US climate opinions, Canadians believe climate change is happening at higher levels. This new opinion data set will support climate policy analysis and climate policy decision making at national, provincial and local levels.

2015 and earlier

Geographic variation in opinions on climate change at state and local scales in the USA

Peter Howe, Matto Mildenberger, Jennifer Marlon & Anthony Leiserowitz. 2015. Nature Climate Change.

Addressing climate change in the United States requires enactment of national, state and local mitigation and adaptation policies. The success of these initiatives depends on public opinion, policy support and behaviours at appropriate scales. Public opinion, however, is typically measured with national surveys that obscure geographic variability across regions, states and localities. Here we present independently validated high-resolution opinion estimates using a multilevel regression and poststratification model. The model accurately predicts climate change beliefs, risk perceptions and policy preferences at the state, congressional district, metropolitan and county levels, using a concise set of demographic and geographic predictors. The analysis finds substantial variation in public opinion across the nation. Nationally, 63% of Americans believe global warming is happening, but county-level estimates range from 43 to 80%, leading to a diversity of political environments for climate policy. These estimates provide an important new source of information for policymakers, educators and scientists to more effectively address the challenges of climate change.

Impacts of the Minamata Convention on Mercury Emissions and Global Deposition from Coal-Fired Power Generation in Asia

Amanda Giang, Leah C. Stokes, David G. Streets, Elizabeth S. Corbitt, & Noelle E. Selin. 2015. Environmental Science and Technology.

We explore implications of the United Nations Minamata Convention on Mercury for emissions from Asian coal-fired power generation, and resulting changes to deposition worldwide by 2050. We use engineering analysis, document analysis, and interviews to construct plausible technology scenarios consistent with the Convention. We translate these scenarios into emissions projections for 2050, and use the GEOS-Chem model to calculate global mercury deposition. Where technology requirements in the Convention are flexibly defined, under a global energy and development scenario that relies heavily on coal, we project ∼90 and 150 Mg·y–1 of avoided power sector emissions for China and India, respectively, in 2050, compared to a scenario in which only current technologies are used. Benefits of this avoided emissions growth are primarily captured regionally, with projected changes in annual average gross deposition over China and India ∼2 and 13 μg·m–2 lower, respectively, than the current technology case. Stricter, but technologically feasible, mercury control requirements in both countries could lead to a combined additional 170 Mg·y–1 avoided emissions. Assuming only current technologies but a global transition away from coal avoids 6% and 36% more emissions than this strict technology scenario under heavy coal use for China and India, respectively.

The Mercury Game: Evaluating a Negotiation Simulation that Teaches Students about Science-Policy Interactions

Leah C. Stokes & Noelle E. Selin. 2014. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences.

Environmental negotiations and policy decisions take place at the science-policy interface. While this is well known within academic literature, it is often difficult to convey how science and policy interact to students in environmental studies and sciences courses. We argue that negotiation simulations, as an experiential learning tool, are one effective way to teach students about how science and policy interact in decision-making. We developed a negotiation simulation, called the mercury game, based on the global mercury treaty negotiations. To evaluate the game, we conducted surveys before and after the game was played in university classrooms across North America. For science students, the simulation communicates how politics and economics affect environmental negotiations. For environmental studies and public policy students, the mercury simulation demonstrates how scientific uncertainty can affect decision-making. Using the mercury game as an educational tool allows students to learn about complex interactions between science and society and develop communication skills.

Effectiveness of a segmental approach to climate policy

Jessika Trancik, Michael Chang, Christina Karapataki, and Leah C. Stokes. 2014. Environmental Science & Technology.

Resistance to adopting a cap on greenhouse gas emissions internationally, and across various national contexts, has encouraged alternative climate change mitigation proposals. These proposals include separately targeting clean energy uptake and demand-side efficiency in individual end-use sectors, an approach to climate change mitigation which we characterize as segmental and technology-centered. A debate has ensued on the detailed implementation of these policies in particular national contexts, but less attention has been paid to the general factors determining the effectiveness of a segmental approach to emissions reduction. We address this topic by probing the interdependencies of segmental policies and their collective ability to control emissions. First, we show for the case of U.S. electricity how the set of suitable energy technologies depends on demand-side efficiency, and changes with the stringency of climate targets. Under a high-efficiency scenario, carbon free technologies must supply 60−80% of U.S. electricity demand to meet an emissions reduction target of 80% below 1990 levels by midcentury. Second, we quantify the enhanced propensity to exceed any intended emissions target with this approach, even if goals are set on both the supply and demand side, due to the multiplicative accumulation of emissions error. For example, a 10% error in complying with separate policies on the demand and supply side would combine to result in a 20% error in emissions. Third, we discuss why despite these risks, the enhanced planning capability of a segmental approach may help counteract growing infrastructural inertia. The emissions reduction impediment due to infrastructural inertia is significant in the electricity sectors of each of the greatest emitters: China, the U.S., and Europe. Commonly cited climate targets are still within reach but, as we show, would require more than a 50% reduction in the carbon intensity of new power plants built in these regions over the next decade.

The politics of renewable energy policies: The case of feed-in tariffs in Ontario, Canada

Leah C. Stokes. 2013. Energy Policy.

Designing and implementing a renewable energy policy involves political decisions and actors. Yet most research on renewable energy policies comparatively evaluates instruments from an economic or technical perspective. This paper presents a case study of Ontario’s feed-in tariff policies between 1997 and 2012 to analyze how the political process affects renewable energy policy design and implementation. Ontario’s policy, although initially successful, has met with increasing resistance over time. The case reveals key political tensions that arise during implementation. First, high-level support for a policy does not necessarily translate into widespread public support, particularly for local deployment. Second, the government often struggles under asymmetric information during price setting, which may weaken the policy’s legitimacy with the public due to higher costs. Third, there is an unacknowledged tension that governments must navigate between policy stability, to spur investment, and adaptive policymaking, to improve policy design. Fourth, when multiple jurisdictions pursue the same policies simultaneously, international political conflict over jobs and innovation may occur. These implementation tensions result from political choices during policy design and present underappreciated challenges to transforming the electricity system. Governments need to critically recognize the political dimension of renewable energy policies to secure sustained political support.