As part of the Public Administration Review's (PAR) symposium on Climate Change and Public Administration, Matto Mildenberger published a commentary on the political benefits of inefficient climate policies. Matto argues that, instead of uncritically enacting climate policies with the least marginal costs, policymakers must consider how climate policy options shape the relative political strengths of different actors over time. As he writes:

"Our atmosphere makes no distinction between a molecule of carbon dioxide released by a coal-fired power plant in Wyoming or by a rainforest fire in Brazil. Yet, the choice to target Wyoming coal or Brazilian deforestation has substantial political repercussions: decisions about who should bear the cost of climate mitigation today reshapes who will have political voice during future rounds of climate policymaking."

One counterintuitive result of this research: policies that are inefficient in the short-term may ultimately produce stronger pro-climate coalitions, and consequently stronger climate policy, over the long-term.

Here is the full commentary:

The political benefits of inefficient climate policies

By: Matto Mildenberger

Climate policy instruments tend to be judged by their efficiency: the ability to reduce carbon pollution at the lowest marginal cost. At first glance, this seems sensible. Transitions to a low-carbon economy will involve substantial adjustment costs. Businesses, workers and publics will face economic disruption and shifting prices. How could we ever justify Pareto-dominated policy designs that impose more costs and spend more money to deliver the same level of carbon pollution reduction? Quite reasonably, it turns out. In fact, serious decarbonization efforts may benefit from inefficient climate policies in the short run when these policies also nurture the growth of pro-climate political coalitions over time.

A move away from “efficiency” can be unsettling. Rhetoric about cost efficiency is deeply engrained within climate policymaking debates. Emissions trading schemes promise to deliver carbon pollution reductions at the point of lowest marginal cost. Carbon offsets and other flexibility-increasing policy mechanisms offer attractive alternatives to costly domestic abatement targets. An undifferentiated carbon tax promises to efficiently price the true costs of carbon pollution into various energy sources. These policies, economists argue, mitigate climate risks in a way that minimizes adjustment costs. Underlying their arguments is an assumption that a ton of carbon pollution abated in one part of the world or in one part of the economy is equivalent to a ton of carbon pollution abated in another part of the world or another part of the economy.

Efficiency or Equity?

At one level this is self-evidently true. Our atmosphere makes no distinction between a molecule of carbon dioxide released by a coal-fired power plant in Wyoming or by a rainforest fire in Brazil. Yet, the choice to target Wyoming coal or Brazilian deforestation has substantial substantial political repercussions: decisions about who should bear the cost of climate mitigation today reshapes who will have political voice during future rounds of climate policymaking. Contrary to the constructed reality of economic models, this means one ton of CO2 reduced in one sector in one part of the world is not the same as a ton of CO2 reduced in a different sector in a different part of the world. Why? These tons may have the same direct effect on atmospheric carbon stocks; however, they have different indirect effects on long-term political support for future climate reforms. The right to release carbon pollution into the atmosphere provides an economic subsidy to particular economic actors. When a carbon polluter is exempted from a carbon tax or given generous emissions allowance allocations, or when a country decides to invest in foreign carbon pollution reduction efforts over domestic reductions, this helps maintain that actors’ profitability and enhances their longevity. In other words, policies that eschew cost imposition on carbon polluters risk entrenching the climate-unfriendly economic and political status quo.

For example, Norway was the second country in the world to enact a carbon tax in 1991 but systematically exempted onshore process industries from any costs for over two decades. (While these industries are now part of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, they joined as clear economic winners under that policy’s allowance distribution scheme). At the same time, carbon taxes on the offshore oil industry were calibrated to avoid radical disruption to that industry’s growth. These exemptions stemmed from the outsized political influence of carbon-intensive industries within Norwegian policymaking debates. Reluctant to impose significant costs on domestic producers, more recent Norwegian governments have championed such initiatives as the Climate and Forestry Initiative, policies explicitly designed to fund low marginal cost carbon pollution abatement opportunities outside of Norway. In this way, efficiency rhetoric has allowed successive Norwegian governments to maintain the political and economic status quo. Current carbon pricing reform efforts face the same political opponents as climate reformers faced in the early 1990s. Meanwhile, domestic emissions have increased 3.3% since 1990.

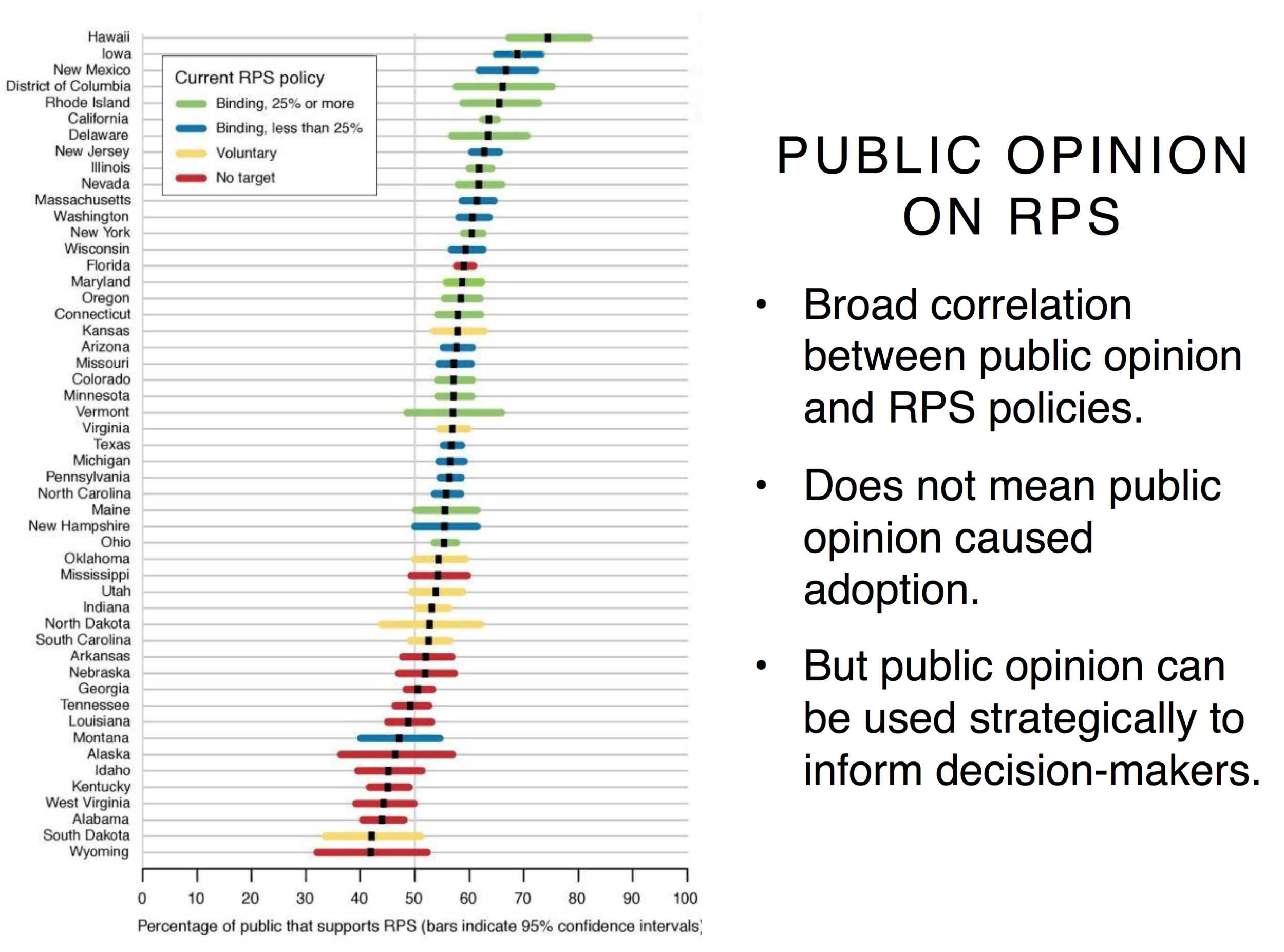

By contrast, inefficient policies can sometimes reshape the distribution of political power when they explicitly redirect resources to new climate policy winners. For example, consider debates over whether renewable energy support policies are desirable after a country passes an emissions trading scheme. In the United States, conservative Democrats opposed the inclusion of a renewable energy standard in the 2009 Waxman-Markey bill because they believed it inefficient and superfluous. Critics suggested the same of Australia’s Clean Energy Finance Corporation, a government-initiated effort to finance clean energy deployment set up in parallel to the country’s emissions trading scheme. According to these critics, mandates for clean energy under a national carbon cap don’t reduce net national emissions; instead, renewable energy deployment simply creates “slack” within allowance markets. In this way, government expenditures on clean energy are wasted on a game of abatement musical chairs without any net mitigation benefits.

Again, this is true in a direct sense. Yet, this criticism neglects a key fact: decisions about the distribution of climate policy costs, even under a cap, have significant political repercussions. When policymakers promote the existence of clean energy businesses, regardless of whether a national carbon cap exists, they nurture new political actors who will mobilize in support of more ambitious future climate policies. Renewable energy support policies promote new political actors that mobilize to support and expand climate and energy reforms. This political benefit can be crucial to long-term decarbonization efforts even if renewable energy support policies are narrowly inefficient in the presence of carbon cap.

Moving beyond marginal abatement costs

In conclusion, public administration scholars need to go beyond merely comparing the marginal abatement costs of different policy instruments, the declaring the one with the lowest to be winner or the desired one. We need to ask whether in some contexts efficiency arguments offer cover for established carbon polluters to avoid domestic costs. Might policies that target higher-cost abatement opportunities facilitate the emergence of new political coalitions to reform existing policies? If it takes inefficient policies in the short-term to support the redistribution of political power in a given economy, will long-term efficiency gains (from the increased political power of pro-climate coalitions) dominate these short-term costs?

The climate threat is not a single-round policy game. It will instead involve repeated rounds of policy bargaining over decades. Consequently, short-term policies must be designed and implemented in a way that generates strategic opportunities for future climate reformers. We must remain open to the possibility that reshaping the balance of domestic political power will cost more than an economist’s estimated least marginal abatement cost. Sometimes it’s the inefficient policies that unlock more effective – and eventually more efficient – decarbonization opportunities over time.

Matto Mildenberger is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University California Santa Barbara.